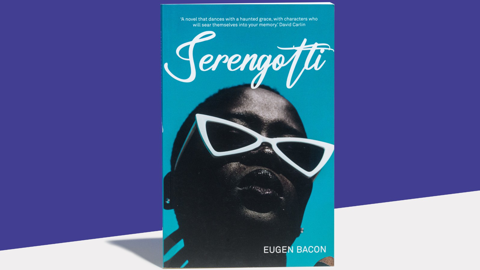

Serengotti

Title: Serengotti

Author: Eugen Bacon

Publisher: Transit Lounge

In the one tumultuous day, Ch’anzu loses hir job and finds wife Scarlet in bed with a stranger. As life unexpectedly spirals out of control, Ch’anzu turns to hir charismatic Aunt Maé for comfort and wisdom, and makes the bold move to work on a project in Serengotti, a migrant African outpost in rural Australia.

In a novel haunted by the strangeness and yearnings of a displaced community – both beautiful and fractured – Ch’anzu is forced to confront hir many demons. Back in the city, brother Tex has gone missing. In Serengotti violence and infidelity simmer.

This is a novel bathed in sensuous, original language, a love letter to the strong women who bind families together despite everything. It’s also a tender remembrance of the many who haven’t or couldn’t survive the dislocations and tragedies of their turbulent pasts.

Photography by Sarah Walker

Judges’ report

Superbly inventive and original, Serengotti is a shimmering, screeching ride from the very opening pages. The confidence and raw energy of the narration makes this an addictive read as it hurtles through one day in the life of Ch’anzu where everything falls apart and catalyses hir move to an African diasporic community set in rural Australia. Nothing is safe or predictable, in this uniquely imaginative, gutsy story of haunting, displacement and simmering violence. This novel brims with the joy of playing with language and storytelling itself, even as it delves deep into traumatic legacies, love, family and the art of survival.

Extract

Along the drive, you’re in your head. Unwilling, resisting but can’t help it, you find your thoughts vacillating around Basket, that strange woman at the aqua centre in Fitzroy.

You’re not exactly electrified about what happened that night. A full moon was out. Maybe it was a harvest moon, or a blood moon. Whatever it was, it messed your head. You had time to kill and you had bathers. Aunt Maé was meeting you to try out this new restaurant called Deguscape that promised African cuisine, and you were on the verge of telling her about Scarlet – how it wasn’t working.

Interkool was unnecessary: you could have skipped it but you wanted to do laps. The staff took your money, gave you a locker, but darn it, not a lap pool. It was more of a leisure hub, resort style with its geometric shape. The water was a clear topaz, the kind you wanted to jump in, just one lane of the pool was shorter than the other. Place was empty bar a couple of old white folk, one of them on his back with a raised leg, doing stretches in trackies on a mat. The other, a woman, was already in the water doing baskets in the longer lane. You called them ‘baskets’ because she was floating on her back and scooping water with her arms and hands in the slowest and shoddiest backstroke you’d ever seen, and all you could think of was collecting water in straw baskets that were losing each drop faster than they filled.

You leaned over, asked in full politeness if you could perhaps take the long end.

She glared at you and, to your astonishment, said, ‘Shut up!’

You tried to explain, ‘I’m swimming laps,’ as patiently as you could – perhaps she might take the shorter lane?

She hissed at you and again said, ‘Shut up!’

So you thought fuck it and dove into the long end anyway, real close each time you swam past her, kicked your legs harder to make a splash. Now you were swimming out of your skin, kicking, kicking, showing off as if you were in a race, the favourite to win it. You were doing some nifty tumble turns – if you dared say so yourself.

Your strokes were ace, you were conserving energy and did another beautiful tumble turn, and you were a dolphin, flap, flap, swim … in your tapered body. You sliced the water with soft hands, and it flowed smoothly over your body, binding between your fingers each perfect stroke.

You felt pumped, as in PUMPED! You were ready to do a one-arm press on the floor tiles. You even did a butterfly, good bounce to it, a real whale in the water, no worries, boasting how decent you swam, not pushing baskets.

The old man was now doing standing calf stretches, his upper body forward, both hands on the wall. He bent slightly, stepped out of it, switched legs.

You flipped, floated your legs, then swept out a backstroke, fingers catching the water, your head still. As you passed Basket, something stung your skin … Had you imagined it? You passed her again, and she pinched you – real nails and fingertips. You hadn’t imagined it. Sure, you’d been the aggressor, and that’s because she’d been unreasonable, but pinching was for kids!

Something snapped, and you stood in the water, your feet touching the metre floor. You heard yourself say, ‘You colonialist! Slave trader!’ It ought to have been a bit funny, maybe not, that you chose to combine two historical averse yet equally suffocating words.

‘It was you —’ she gasped.

‘You belong in a jail of colonialists and slave traders!’

Then you saw the old man by the water’s edge. Clearly they were together – the way he was eyeballing you.

‘I am younger and stronger than you,’ you said, loud, for his benefit. ‘Touch me one more time and I will hurt you.’

She scoffed at your fact.

Your mood was irrational, call it OTT. Had the pinches broken off skin? No. You felt something raw inside, but it was not ire: it was a culmination of topsy turvies, and you were tired of being picked on.

The old man by the pool … You thought he’d pin-drop into the water, reach your collarbone in two strides. But his body was unwilling. He stuttered out of his trackies, dipped into the topaz water, to do … what? Give moral support? He looked at you severely, but his body was at odds with his self. He swam in your direction, towards where you were arguing with the woman.

‘I saw you start —’ he shouted.

‘Is she your wife?’ you demanded.

‘You were the one —’

‘Teach her manners,’ you snapped. ‘She has no right to pinch me.’

‘But you —’

‘The days of oppressing black people are over. Tell her that!’

The her in question wasn’t lingering to see if her man was inclined to tell anything or teach manners for her benefit. She progressed her baskets as you and her friend, lover or hubby yelled at each other. Then he too – bushed after the heated exchange – turned away, as if happy to forget it, and was content to gasp and wheeze back and forth along the lane.

You swam the rest of your laps, but they were no longer on a good float, no longer easy in the water. The old man still swam, croaking and wheezing each stroke. You pulled out of the water, entered the spa. You sat facing the pool, scowled at him when he groaned and gulped in your direction.

Maybe it was your laps, the blood still running. Or your moral outrage over a grown-woman pinch. Whatever it was – you do have a knack of bounding into storms – you refused to let it go with Basket. Every now and then you remembered – this was not kindergarten, who pinched people? You helped her recollect, even as she continued to ignore you and your aimed-to-wound words: ‘Slave trader! Colonialist!’

She stayed oblivious.

He looked worse for wear each splash with his hands. As warm bubbles licked you, you wondered if he might cark it any moment. And then you thought: Bloody hell, you’re a first aider. If she carks it, you’ll have to dive in the water and resuscitate the bloody bitch.

Thankfully, as your spa foamed and gurgled, neither of them croaked.

On your way from the poolside, you glared at the two with the best hellfire you could churn inside your eyeballs, but your words came out calm. ‘Get yourself a pet monkey.’

Basket laughed or gasped, moved her mouth up and down in silent words you couldn’t decipher. Then her eyes widened, a heart attack coming, and you legged it out of there.

Aunt Maé had already arrived, but Deguscape wasn’t all that. The most African its cuisine got was an ‘African souvlaki’, then a swirl lava cake named ‘The Mount Kili’ that the chef and his menu determined was ‘inspired by the craters of the Ng’orong’oro’. It was more of a dirty hillock that tasted bland – the insipid flavour of shame. You pulled your face, swallowing a mudful.

‘Something happened?’ asked Auntie.

‘Mmhh?’

‘Your face. Like a seven-tonne ball has just bounced off it.’

‘Gee, thanks.’

You nearly told her then about Basket – you couldn’t believe you’d said it: Get yourself a pet monkey? You’d overstepped the mark and, in truth, the old woman was only protecting her baskets, not being racist, when you crashed into her swim lane. Sure thing, she’d said, Shut up, and that worked you wrong. But a pet monkey?

Maybe you were having a bad moment, a Scarlet overflow? Things weren’t working with your wife, and it was bringing on meltdowns.

But you didn’t tell Auntie any of that: instead, you said, ‘I don’t want to gob about it.’

She touched your hand in that comforting way of hers. ‘It’s just us. With me, you can chitter-chatter like a little chipmunk – see if I’ll mind.’

You laughed, and the matter was finished.

The bill cost a spleen, but Aunt Maé wordlessly fished out her wallet, would hear nothing about splitting, even left a tip that you joked about. ‘That cost a kidney with all the stones removed. Are you paying them to make sure they don’t harvest any more of your organs?’

She laughed it off. ‘Aw, shut up,’ she said. ‘Thanks muchly, Thrifty, that’s enough.’ She drove you home and said, ‘Be good now,’ as if aware of all the mischief you’d caused that evening.

You quietly slipped into your side on cool sheets, and Scarlet – who no longer tossed a hungry arm across your empty pillow – did not stir.

That night you dreamt of a curse, unspoken yet loud. Wafting out in slow motion from Basket’s gasping mouth, opening and closing. Frothing out her ominous words that in your dream said: What you deserve. Is. Coming. For. You.