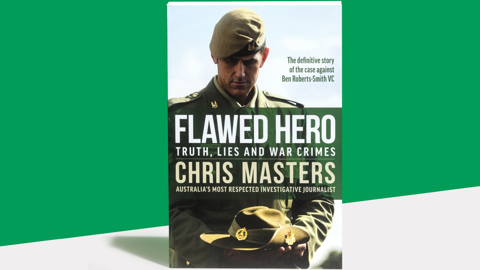

Flawed Hero: Truth, lies and war crimes

Title: Flawed Hero: Truth, lies and war crimes

Author: Chris Masters

Publisher: Allen & Unwin

The shocking story of the case against Australia’s most highly decorated soldier, Ben Roberts-Smith VC MG, and the defamation trial of the century.

With a Victoria Cross and Medal for Gallantry, Ben Roberts-Smith was the most highly decorated Australian soldier, the best of the best. When he returned to civilian life, he became a poster boy for a nation hungry for warrior heroes. He embodied the myth of the classic Anzac, seven-foot-tall and bulletproof. But as his public reputation continued to grow, inside the army rumours were circulating.

Gold Walkley Award winning journalist Chris Masters was the first to investigate the rumours of summary executions, bloodings and bullying, and began to examine more closely the man we wanted to hero-worship. When the stories hit the headlines, and with a billionaire media baron’s backing, Ben Roberts-Smith sued. So commenced the defamation trial of the century, a courtroom contest of tightrope tactics and fierce wit.

Chris Masters tells the extraordinary story of Ben Roberts-Smith, the man at the centre of this de facto war crimes trial, from the battlegrounds of Afghanistan to the front lines of the Federal Court.

Photography by Sarah Walker

Judges’ report

Chris Masters’ Flawed Hero: Truth, lies and war crimes is a world-class forensic work of investigative journalism. With unprecedented access, the story spans Masters’ decades-long coverage of the Australian Defence Force and unveils the killing-machine persona of Australia’s most decorated soldier Ben Roberts-Smith. At the heart of Masters’ work is a defamation trial that calls to question the truth of his allegations against Roberts-Smith, underlying the proceedings is a challenge to the myth of an infallible Anzac spirit, a challenge to the mirage of heroism, and a challenge to the misuse of truth by those with power.

Extract

A rumour of war crimes

The common representation of investigative journalists at work involves sneaky meetings with Deep Throats in underground car parks. People telling us stuff, which is then converted into breathless revelations.

It is sometimes like that. But more often interactions are abstract, and the discovery process is internal. Lots of engagement with truth-tellers and liars, and lots of reading between the lines. The investigative journalist’s beat is quicksand and shadowland.

Mostly it is about figuring something out. And that is how this one went.

It was 11 September 2011, the tenth anniversary of the terrorist attacks in the United States that triggered Australia’s longest war. I was finding my feet in the Australian Special Forces compound, Camp Russell, having arrived a few days earlier. It was my third embed with Australian soldiers in Afghanistan.

To the soldiers, my presence was unthinkable—that a journalist would have the code to the keypad entry at their uber-secret enclave. At many stages up to this point, it was unthinkable even to me. But there I was: the first and, as it happens, the last journalist to be granted access.

The simple explanation is trust.

My reporting over the preceding decade had been supportive of the soldiers and their mission. I never thought we were on the wrong side in Afghanistan. I believed that, back at home, our country’s humanitarian objectives and complex challenges were poorly understood. I admired the selfless bravery of Australian soldiers stepping out, with their fingers off the trigger and yet at great risk of being blown to bits, so as to provide a protective screen for a blighted people.

I had seen Australians at war (or, more precisely, engaged in peace-keeping missions) many times before. In Timor, a villager had enthused to me his heartfelt astonishment that soldiers were there to shield them from danger. ‘We hide our daughters when men in uniform appear,’ he said. ‘We think of them as bandits.’

In Rwanda, the Australian Special Air Service Regiment (SASR, but commonly known as the SAS) had faced off against genocidal mobs, risking their lives to dampen rather than inflame violence. In Somalia, young soldiers of the 1st Battalion of the Royal Australian Regiment (1RAR) had patrolled aid posts and raced in to fight thugs who were bashing starving women and children out of the way so they could steal and resell lifesaving provisions.

For me, Australia’s reputation for civilised soldiering, for toughness and fairness, held up. I was inspired—somewhat romantically, I admit—by a belief that Australian major general John Cantwell had expressed in an interview with me: ‘There is something about the Australian character that is suited to the things soldiers are asked to do.’

The soldiers saw my belief in what they were doing. So, to some degree, I was trusted. Of course, I would remind them that I would report bad behaviour if I ever saw it—but nobody took much notice of that, because nobody expected it to occur, especially in front of a camera.

The goodwill I enjoyed among the soldiers was probably equal in strength to the misgivings about me within the ranks of my fellow journalists. There were plenty in the news business who were convinced I’d been ‘captured’ by the Australian Army. Some saw me as a flake, a flunky—Major Masters of Defence Public Relations. The great Dr Johnson believed that ‘every man thinks meanly of himself for not having been a soldier’; perhaps I was an example.

During my embed, I saw only a little of what would later initiate some searching questions. It was mainly that quick glimpse of hatred in the eyes of Afghans before they were blindfolded and brought back for questioning. Yes, I was admiring, but not to the degree of suspending scepticism, a critical attribute in the armoury of any journalist.

What really counted was that the soldiers’ trust in me led some of them to share their concerns—not all at once, but over time. The irony is unmissable. While plenty of reporters had set out to uncover war crimes, the first team to do so was not so narrowly focused.

This is another feature of investigative journalism. Revelation rarely comes in a blinding flash. It is usually a graduated light of truth that steers you along an unanticipated path.

When my first book covering Australian operations in Afghanistan, Uncommon Soldier, was published in 2012, it included references to the famous soldier Ben Roberts-Smith. At the time I checked my text with him and he asked for some amendments. The action in 2006 that had earned him a Medal for Gallantry I described in my book as follows:

On 2 June, Ben Roberts-Smith was forced to fight for his life when his observation post came under attack from two flanks. He split and manoeuvred from his team, catching sixteen approaching enemy in the open. Roberts-Smith took them on with his sniper rifle, attracting accurate return fire but holding the enemy off for the forty minutes it took for air support to arrive.2

What I wrote fell short of a more complete truth.

I had not depicted it as a war crime, but this incident atop a barren mountain range in southern Afghanistan would trigger the largest war crimes inquiry in Australian history.