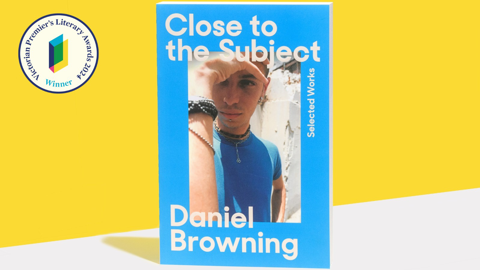

Close to the Subject: Selected Works

Title: Close to the Subject: Selected Works

Author: Daniel Browning

Publisher: Magabala Books

This book is a collected works of one of Australia’s most accomplished media personalities. Chronicling his career since 2007, Close to the Subject presents a selection of pieces from Daniel Browning’s stellar career as a journalist, radio broadcaster, critic and interviewer. Alongside conversations with the likes of the late Archie Roach, Doris Pilkington, and Vernon Ah Kee, the book contains a series of critical essays displaying Browning’s talent as an Australian cultural critic and public intellectual. A range of previously unpublished poetry, memoir, art writing and play script is also presented, highlighting his vulnerable and passionate creative side in its own right.

Photography by Sarah Walker

Judges’ report

Close to the Subject: Selected Works is an astounding contribution to arts journalism by one of the most significant writers in the field, parsing over twenty years of Indigenous art, politics, and cultural life. Bundjalung and Kullilli journalist and writer Daniel Browning’s cutting and sensitive book threads poetry, memoir, interviews, and criticism into what is simultaneously vital historical record and a vision of new directions in arts writing.

Extract

Introduction

I am a storyteller – nothing more. As a journalist I have often speculated on the place where I sit, my positionality on the spectrum of positionalities, and where my writing fits among the genres of storytelling. It is probably another vain and pointless exercise, given the polarised nature of the media in Australia (Murdoch and the rest). Another thing that obscures my work is the public appetite for and newsworthiness of stories which represent blackfellas as broken and dysfunctional. This meta narrative drove the hysteria and nightly horror of sexual abuse claims in remote Indigenous communities since disproven which led to the Howard government’s military-assisted Northern Territory Emergency Response in 2007. There are other ideas, tropes and fantasies that mystify who we are – for example a wilful blindness to our suffering as self-inflicted, utterly disconnected from the original sin of dispossession. An almost blithe disengagement with ‘our’ issues as too complex and marginal not to mention the strange idea that our ‘voice’ should be singular and unilateral also complicates matters. For years it was standard media practice to put up one rancorous, newsworthy voice from the unelected, right-wing black commentariat on any particular issue and that was that.

Precisely because we are supposed to be incapable of objec-tivity, and therefore not to be trusted, we are often excluded from the national conversation – of which we are sometimes the subject. The moral panic over youth violence and lawless-ness on the streets of Alice Springs – fed by overheated media reporting – is a good example. In such debates, our collective rage or apathy is pathologised – we don’t know our own minds, we can’t agree, or we can’t articulate what we feel or know in terms that whitefellas and other settlers can understand. According to this twisted logic, it seems to follow that we are stupid, we are undeserving, and even – in the worst case scenario – a broken people without hope. That we are like every other population group with many strident voices (on a matter as significant as constitutional recognition and the Voice to Parliament, for instance) is always characterised as a fault. Broadly I have tried to puncture the silence and mystification that constellates around the thing we call Aboriginal art. But at a deeper level I have always tried to give voice – to literally surrender the microphone (another example perhaps of how antithetical my practice is to the profession).

It reminds me of a moment that perfectly illustrates the fine balance and compromise we as Indigenous journalists have to strike. A senior artist from an artmaking community in the East Kimberley had won a generous biennial prize for her entire body of work, canvases loaded with black and white ochre mined on her country with spare iconography drawn exclusively from the one ancestral story. She was in a wheel-chair in a gallery in Melbourne which had been hung with her almost calligraphic paintings. I sat opposite her with my trusty brick-shaped 702 Sound Devices recorder and a well-travelled microphone. I leant in, and as I finished my first question she did the strangest thing. She gently slipped her long fingers around the mic and, completely ignoring my question, told the story that animated her work. Her microphone technique was such that she popped wildly on the plosives, and parts of the recording were so badly affected by peak distortion that it could not be salvaged. I could have simply wrested the mic away, but at that moment it seemed too brusque, even disrespectful – if not extremely rude. Instead, I listened deferentially as she pointed out the almost totemic signs of a superhuman odyssey, feeding back on itself in an eternal loop.

It may seem insignificant but in that moment I had a choice: be a journalist or be a blackfella. And I’m here to tell you that it wasn’t the first or indeed the last time. Unless we excuse ourselves from the network of social responsibilities that we are born to, those obligations – to deference, avoidance, asset sharing – can and will complicate what we do. For years I made it a policy not to report on my own community, despite there being occasion to do so, because I didn’t want to be targeted by my bosses and accused of bias, of subjective journalism, and a failure to uphold the ethics that bind those journalists who actually believe in the profession – who exercise its power and discharge its responsi-bilities. By the same token, the idea that the only value of my work is in its embedded blackfella subjectivity is also an assump-tion worth challenging. As a black journalist, I have covered the entire spectrum of generalist news reporting including federal elections, state politics, courts, police and emergency rounds, the arts, sport and youth affairs. Black journalists belong in every newsroom, covering every story; but despite reaching critical mass, not every newsroom or media outlet will welcome us or publish the stories we write. We will be trailed by the stink of their assumptions – that we are undeserving, incapable of their standards of objectivity and can’t be trusted as journalists.

The risk I have run in unmaking journalism to make it less culturally unsafe and more inclusive has paid off, while sepa-rating me from my white colleagues who stand by a kind of editorial distance I can’t even fake. I have enjoyed rare access to some extraordinary, unstintingly generous people. I have knelt down and breathed dust, inhaled the cleansing fumes of burning eucalypts and been humbled by the experience. I have walked country and held axes and grinding stones laid down by the ancestors in the shadow of drought and glaciation as their teeming rivers dried up 15,000 years ago. I have watched their bones return home. I have tracked intrepid ancestors who explode the historical myth of an isolated, defeated and incu-rious people without power and agency confined to missions and reserves. I have seen the bullets lodged in shields once borne by our warriors but now secreted in drawers in the tempera-ture-controlled vaults of natural history museums overseas.

I have listened to stories of soul-crushing cruelty told by the survivors of a notorious Aboriginal boys’ home; how they were welcomed with the balled fists of a sadistic manager who did much worse while they were chained to a Moreton Bay fig tree in the grounds of the home. Of children separated from their kin on the bustling platforms of Sydney’s Central Railway Station as commuters passed, blind to the obscenely public tragedy unfolding before their eyes, and wept for the loss of innocence. I have watched an ailing, now finished senior artist shift in her wheelchair to sing up to her painting in the National Gallery of Australia. I have listened to another, also now finished, describe the buffalo attack that maimed her but which triggered a conceptual leap; a radical departure that bridged the moment of creation in ancestral stories with individual memory, the earthly and the corporeal. I have seen the anguished faces etched in the rock of the sandstone escarpment where militiamen forced Dharawal to their deaths in the undeclared war of 1817. I have listened to the Pitjantjatjara version of the wanambi story that animates the canvases and churns the riverbeds and waterholes of the Central Desert. To create a monument in sound, I have spun a bullroarer just like those that summoned the initiated to men’s business on K’gari, and miked the low thud of a possum skin drum stretched across the lap of a Wiradjuri woman.